pedagogy

Trigonometry is a field of mathematics concerning functions that deal with angles (sine, cosine, secant). Don’t be fooled by this relatively humble description, however (I believe I’ve committed a heinous crime by describing trigonometry that way) — as it is some of the most important mathematics to have ever been done, and has countless applications across the fields of physics and engineering.

Despite the gravity with which trigonometry holds within the mathematical world, it is universally hated by math students across all grade levels and continents. If trigonometry is such an important subject, and is one that does not require extensive knowledge of to be useful in its various applications in physics and engineering, why does it receive so much hate? Of course, the answer lies within the actual teaching of the subject.

i hate trig why do i need this in my life

— Rory! 78 • 19 (@conansstar) April 25, 2023

i fucking hate trig who invented this shit its disgusting

— rai 🇵🇭 (@padsplswin) April 27, 2023

From my own experience as a high school student, trigonometry is taught like this:

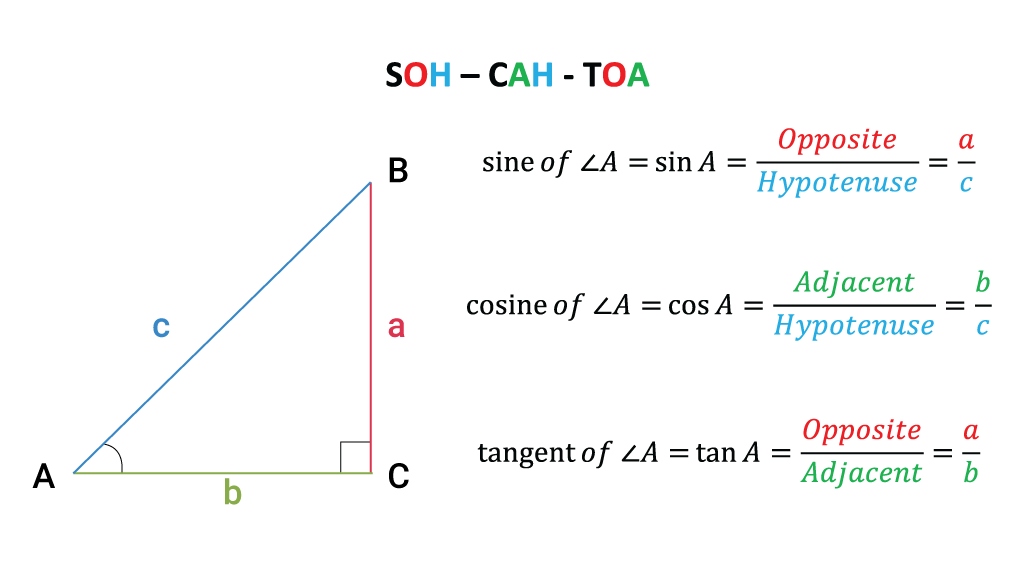

You are taught this “SOH-CAH-TOA” mnemonic, to memorize parts of a triangle, and then blindly plug in numbers into a calculator to obtain the result that you want. Of course students of trigonometry hate it — this teaches them nothing about what trigonometry actually is!

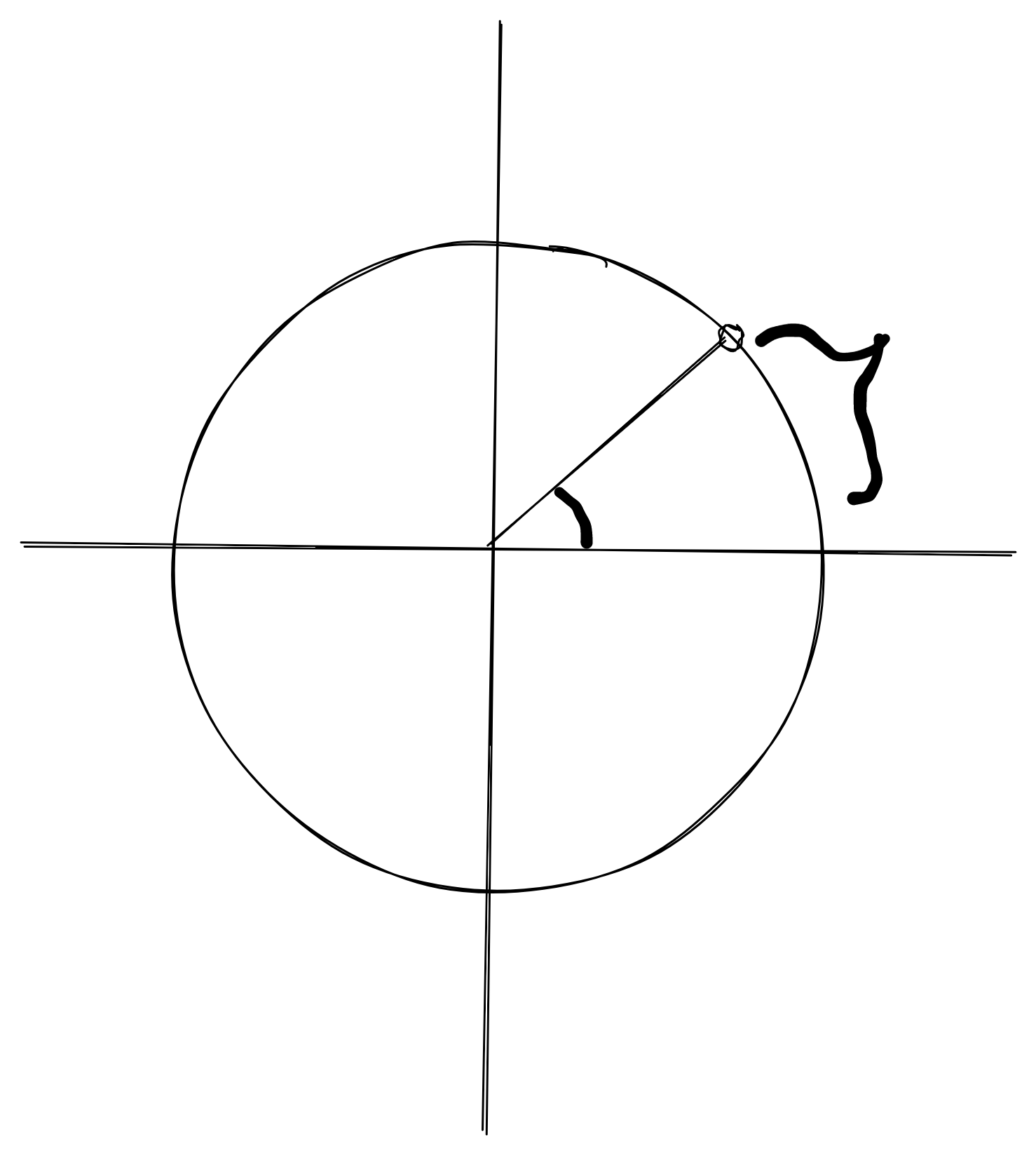

Trigonometry is a lot easier to think about when you relate it to circles — not triangles. Picture a perfect circle with radius 1, a point on that circle, and a number d. This number d represents the angle in degrees that point has with respect to the x-axis — feel free to play around with it and observe how the point moves around the circle.

Note that this circle is embedded into a Cartesian plane with its center at the origin. What if we were to add another point that stays put with respect to the x-axis, but mimics the original point’s motion along the y-axis?

Notice how this point moves along the y-axis in an oscillating, wave-like pattern. What if we were to do the same, but for motion along the x-axis?

Finally, let’s remove the circle, and graph the motion of these points as we change the angle, with the x-axis representing the angle and the y-axis representing each point’s respective magnitude. By “magnitude”, I mean the y-value of the point that mimics motion along the y-axis, and the x-value of the point that mimics motion along the x-axis.

Turns out, the point that mimics the motion along the y-axis represents the sine curve, and the point that mimics the motion along the x-axis represents the cosine curve! Finally, we have a tangible representation for what these functions actually model! As you increase the degree of the angle, the sine function represents the y-value or the “height” of the point that you end up at, while the cosine function represents the x-value or the “distance from the origin” of the point that you end up at.

Of course, I can only do so much with Desmos embeddings and text. For a much clearer explanation of the concepts discussed above, watch Grant Sanderson’s excellent video on the topic. He explains it much like I do.

Another problem that students run into when learning trigonometry is the switch from degrees to radians. For many students, degrees are intuitive — sure, their values may be arbitrary, but they benefit from familiarity. Radians, on the other hand, is an unfamiliar standard of measurement — students often question what the significance of π in representing angles.

The trick lies by switching our perspective of where the angle “exists” instead to the length of the arc tracing the rightmost edge of the circle to any arbitrary point on the circle:

You might recall that angles are typically represented by that small arc near the center of the circle — what I want you to do now is to focus instead on the much larger arc represented by the circumference of the circle. Then, imagine a point on the topmost part of the circle — instead of representing that angle as 90 degrees, we now represent it by the arc length running from the rightmost part of the circle to the topmost, which you’ll observe to be exactly a quarter of the total circumference. With a radius of 1, this would be \(\frac{\pi}{2}\). Of course, we can’t always assume that the radius will be one, which is why we need to generalize this measurement — instead of saying the angle is \(\frac{\pi}{2}\), we say it is \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) radiuses, or radians.

Tangent aside (pun not intended), the conclusion that I want you, the reader, to arrive at, is that in a learning environment, we cannot present knowledge as-is. Most knowledge, as you might observe, does not exist “as-is” — it has a history, it has motivations, it has a reason for being in that form. If we do not fully explain how certain knowledge came to be, the motivation behind the knowledge existing in the first place, and the reason the knowledge exists as it does today, then we fail to teach.

I’m happy to say that although I’ve never attended a university-level class in an actual college setting, I’m an avid viewer of recorded college lectures online and I’ve observed professors dedicate portions of their lecture to present the motivations behind teaching a certain subject. While this is a step in the right direction, the unfortunate truth is that a significant amount of teachers today, especially in the foundation years that are the elementary and middle school stages, do not perform this simple task — and by doing so, they rob students of crucial knowledge that provides a foundation for all their future thinking to rest upon. What’s even more unfortunate, is that some teachers can’t help it — they themselves were victims of teachers that failed to do this simple task.