power of nonlinearity

Skip to the next section if you’re unfamiliar with the underlying neural network mathematics

The neural network is a fundamental idea that powers many AI systems we have today. It has been scaled up to tackle hard problems such as natural language understanding, object recognition, driving, and many other abilities thought to be exclusive only to humans.

Rant

The idea that intelligence is exclusive to a carbon-based neural network such as the brain is absurd. Any sort of computation that the brain performs to transform electrical signals into coherent thought can and will be done by silicon. The problem is figuring out the computations in the first place.

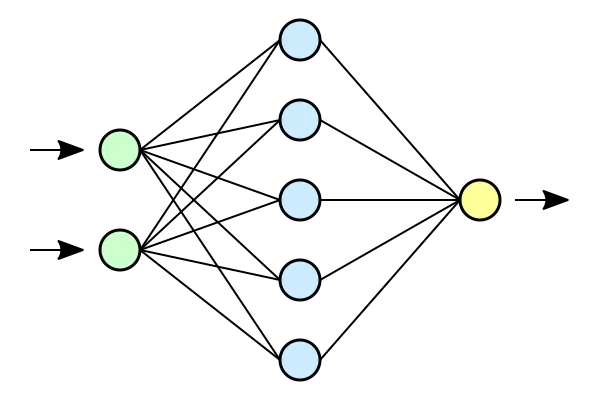

The following is a multi-layer feedforward neural network as it is commonly visualized, and how they’re commonly explained:

A single “neuron” in this network has a “weight” and a “bias”. The neuron takes in a real-valued number as input, and transforms it according to the following equation:

It then feeds the result to the next layer.

Thinking about neural networks this way is messy. Instead, we take a different route. Let’s think about the input as being a vector, and we pass this vector input to each layer as a whole, instead of thinking about passing separate numbers to each neuron.

Then, if you work out the math, you’ll realize that the linear transformations being performed by each neuron, if you consider them as a whole, is analogous to a matrix vector product. In fact, it is exactly a matrix vector product — we aggregate the weight vectors in each neuron to one large weight matrix, and each bias in each neuron to one large bias vector. Then, the computation being done by a single layer can be represented elegantly with this one-liner:

where \(l_W\) is the weight matrix, and \(l_b\) is the bias vector.

Then, neural networks can be simply thought of as a series of linear transformations to data!

Why linear transformations are useful

A linear transformation is a function that takes in a coordinate, and maps it to a different coordinate in Euclidean space. However, the transformation is only classified as linear if grid lines remain parallel and evenly spaced.

Matrices are linear transformations — performing a matrix vector product with a 2x2 matrix on a 2-vector results in another 2-vector. 2-vectors are just vectors with 2 dimensions; therefore, you can extend the idea of a coordinate to a 2-vector.

We can combine linear transformations to perform prediction on data.

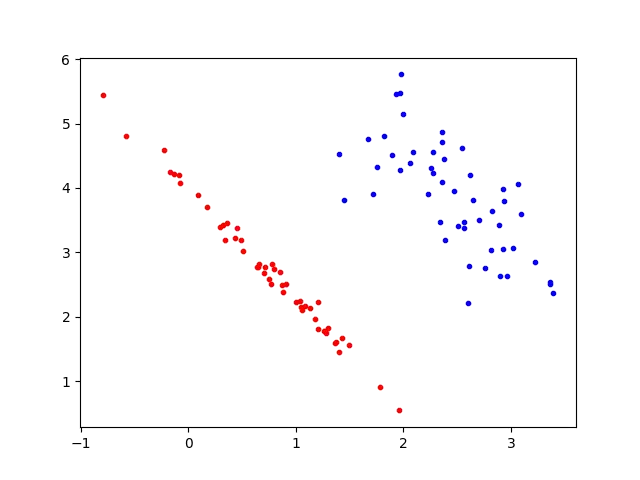

For example, take the following scatter plot:

If we wanted to come up with our own series of linear transformations to categorise this data, we might come up with the following:

Rotation — Imagine the linear boundary between both groups. We rotate the data such that that linear boundary is now horizontal:

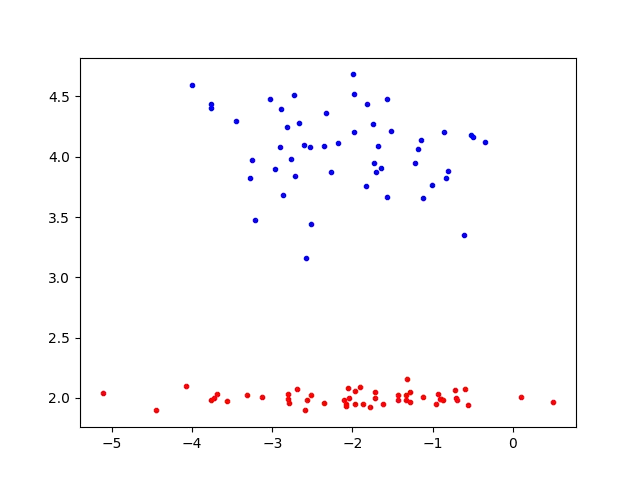

Translation — Now, with the rotation being done, our next transformation is not actually a linear transformation, but rather a translation along the y-axis such that both groups are separated by the y-axis, through the use of a bias vector instead of a weight matrix:

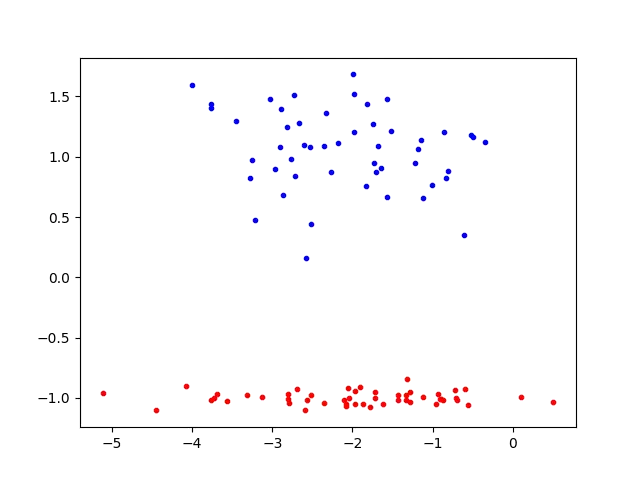

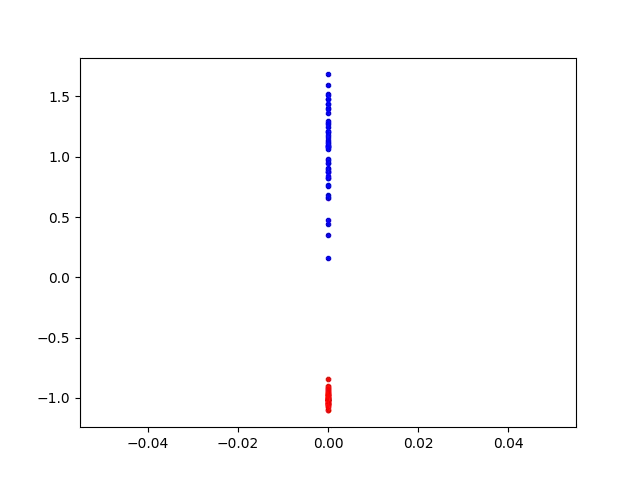

“Squeeze” — Now, we use a singular matrix to transform the data from 2D Euclidean space to 1D Euclidean space, preserving the y-coordinate:

Now, our hypothetical neural network’s outputs can be easily interpretable — anything less than 0 is part of the “red” class, and anything above 0 is part of the “blue” class.

These three linear transformations don’t need to be in separate layers, either — they can be easily combined to one layer, by multiplying them all: \(L=l_3⋅l_2⋅l_1\).

But how about more complex data?

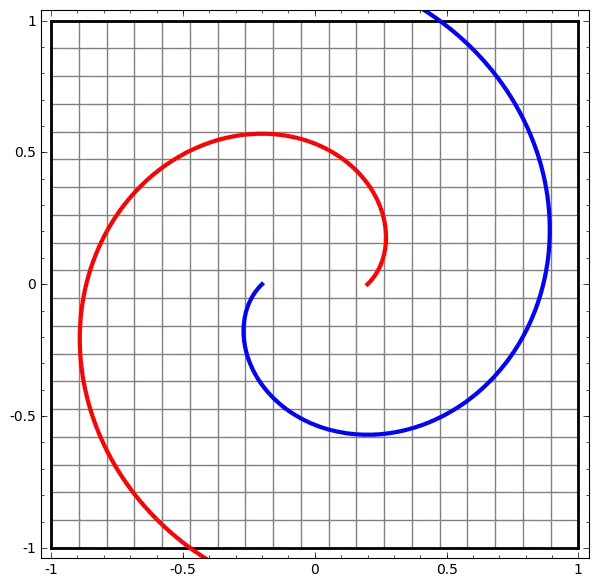

Not all data is linearly separable by default. For example, observe this scatter plot:

There is no obvious linear pattern we can observe here. Therefore, we have to make our linear transformations non-linear, and we do that by interspersing them with nonlinear functions:

where \(σ\) is any arbitrary nonlinear function.

With this added functionality, here’s a visualization of how a nonlinear function can transform nonlinear data into linear data:

Linearly separable data is much easier to deal with!

Conclusion

In this article, we showed that neural networks (at least, the feed-forward neural network) are not what they are commonly compared to — biological neural networks. Instead, they are a series of linear transformations in the form of matrix vector products, interspersed with nonlinearities.

This fundamental idea of composing “non-linear linear transformations” has led to many breakthroughs in the field of AI; namely, convolutional neural networks in the field of computer vision, transformer networks in the field of natural language understanding, and LSTMs in the field of general time-series forecasting. With parameter counts reaching up to the hundreds of billions, it is not hard to see that this basic idea of stacking transformations can tackle much higher-dimensional data such as images and natural language.